The widespread understanding that universities are failing to intercept social plagiarism (e.g., this Irish report) creates pressure on the sector to establish tools and practices of detection. Alin (2020) offers one review of institutional options. David Tomar gives advice as an experienced ghostwriter (note how the modest respectability of this term makes it preferable to ‘contract cheating agent’). That alliterative advice is: ‘detection’ ‘deterrence’ and (assignment) ‘design’. His portfolio-based suggestions on detection are actually derived from advice given by the New Zealand Qualifications Authority, who note that: “seeing a collection of a student’s work within one portfolio will make inconsistencies obvious. It also enables managers/tutors to set tasks that rely on personal situations, unique data”.

It is fair to suggest that all methods of detection are based on this principle: collect a corpus of student work and be alert for spikes of inconsistent performance or style. This is a daunting task for hard-pressed lecturers to take on: however, the text below identifies some obstacles but also some possible approaches.

Individual thresholds for possible offence

There is now widespread understanding among staff that the contract cheating version of social plagiarism is a real phenomenon and a matter of necessary concern. Awdry and Newton (2016) surveyed 196 staff from various faculties in Australian and UK universities and found that most had experience of these problems, while reporting their view that typical outcomes were lenient. While there may be a will to identify these cases, one obstacle to effective ‘manual’ detection is the fact that lecturers may differ among themselves as to how an offence is both determined and then acted upon. More recently, Harper et al (2018) surveyed 1147 staff from Australian universities (a return representing 7.3% of total numbers). They note:

Almost 70% of teaching staff have suspected outsourced assignments at least once… Nearly half the staff who have suspected seeing outsourced assessments reported that they typically manage these cases themselves, rather than refer them on to an academic integrity decisionmaker… While staff reported a range of reasons for managing contract cheating themselves, the most common response was that ‘it is impossible to prove’

Coren (2011) has also identified the emotional strain of engaging with these problems, studying responses to a survey instrument that measured faculty attitudes to cheating. The instrument was applied to 852 staff at both a US and a Canadian university (a response rate of 24%). It was found that staff with previous bad experiences of cheating were more likely to deal with it now by ignoring it. These staff had come to feel more stressed when speaking to students about cheating and they admitted to preferring avoidance of these emotionally charged situations.

Individual academics in our own research samples made comments that highlighted the sense in which discretion and stress surrounded the management of social plagiarism cases:

..my predecessor thought that students always got the benefit of the doubt in appeals cases, so he thought we would need a water tight case if anything went to appeals. My sense amongst colleagues is that we don’t penalise cheating enough

..because a lot of the time you think – why is the student doing this? Why have they fallen into doing this? Is there something else going on? Which doesn’t excuse this kind of, but it kind of explains it. And then you are in a position to probably kind of impose less of a sanction and try and understand what’s gone wrong, and to sort things out in a way that helps them.

So, you’ve opened a door where the chance is you’re going to penalise people in ways which are wholly unfair. And, even the cases where you’re pretty convinced that they’re colluding because you know the student and what they do in seminars or whatever, I just don’t think you can make that call

Then if I have put this [untypical student writing] through as an academic offence, that’s calling into question this person’s integrity. The relationship then between tutor and student is damaged. I’m going to go and meet this person again. We’ve got more face to face teaching to do. That’s quite an insult really. If this person has written this, even though it misses the mark in the ways I’ve said, that’s a huge achievement in some ways in terms of the coherence of it, compared to what they did before. To say, “I don’t believe you wrote that.” is quite a big step. So that leaves me with that dilemma really.

Similar reactions have also been reported from academics surveyed on academic dishonesty management within one South African University (Thomas and De Bruin, 2012)

Detection ability of assignment examiners

Rogerson (2017) provides guidance on the kind of assignment features that might be indicative of a contracted author. These include misrepresented bibliographic data, inappropriate references, irrelevant material, and generalised text that did not address the assessment question. However, it is also urged that any suspicions derived from ‘manual’ scrutiny of student work should be complemented with exploratory conversations involving the students implicated. Such conversations can be assumed to be taxing but also time-consuming.

The ability to pick up these cues to a social plagiarism offence has been examined by Dawson, and colleagues (2018, 2019) in a study where seven experienced examiners were paid to individually blind mark twenty Psychology assignments. These were split 14/6 real student assignments versus purchased assignments; markers were primed that the study concerned contract cheating. Because the results were inappropriately summarised, it is only possible to conclude that the two sets of assignments were discriminated quite well, implying that contracted essays may have inherent features that stand out – independently of a requirement to benchmark against the students’ normal work.

Automating the detection process

It is difficult to generalise around the kind of stylistic markers that might suggest an assignment text looks as if it has features that a course student might not have used. Here is one example of what might be looked for.

Clare et al (2017) consider whether detection of anomalous assignments might be automated on the basis of machine analyzing the assessment performance history of students. Using data from the Law School of one Australian university, 3798 assessment results were analysed from 1459 students. The analysis sought unusual patterns of results. Approximately 2% of students produced patterns that were consistent with contracted cheating. Evidently this method could be adopted as a relatively simple administrative task to be used as a triage process.

The next level of automation would involve textual analysis of a student’s corpus of work, looking for anomalies at the level of writing style. Stylometry provides a basis for thinking this might be possible and there are already online services such as Emma that perform quite well. Alzahrani et al (2011) have reviewed techniques that would be appropriate for a such a corpus of essays. Although it is important to remember that essays are not the only material that needs to be checked in this way – for example, Novak (2016) considers stylometric tools that can deal with source code plagiarism in Computer Science assignments.

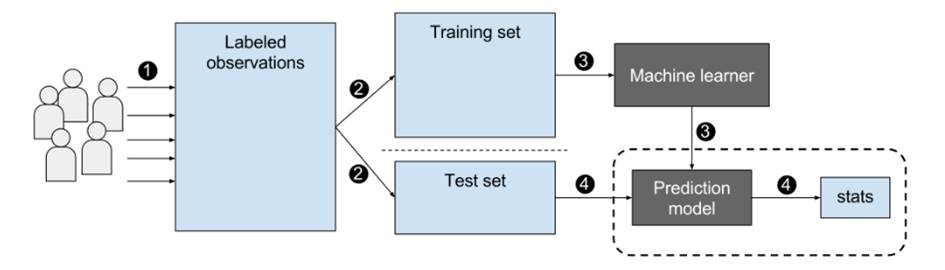

Amigud et al (2017) have published empirical findings derived from a machine-learning based framework capable of constructing students’ differing patterns of language use. (Baneres et al (2016) outline the principles behind this method). They report a series of experiments on twenty assignments ranging between 1000 and 6000 words and submitted by five graduate students at an online European university. The method was able to map student-produced content with 93% accuracy. While instructors performed at the significantly lower rate of 12%.

If such methods are to gain traction, they may need to be integrated with existing university systems for administering assessment. Mellar et al (2018) describe TeSLA (an Adaptive Trust-based e-assessment System for Learning), a project which is developing a system intended for integration with Virtual Learning Environments and which would provide a variety of instruments to assure student authentication and authorship checking. This family of problems is acute in the case of online courses (which are the main concern of these authors). The methods of authentication they are investigating include Face Recognition, Voice Recognition and Keystroke Dynamics (for typing rhythm) while, in order to check authorship, there is included a Forensic Analysis (for writing style) and a Plagiarism Detection mechanism.

A more ethically controversial application of AI involves its deployment to roam outsourcing sites – masquerading as one itself. The system then sets traps for student customers in which it “identifies posted homework assignments, and provides students with watermarked solutions that can be automatically identified upon submission of the assignment” (Graziano et al 2019)

The commercialisation of detection processes will doubtless happen. For example Turnitin now has a new system ‘Authorship investigate’ – described more fully here as a method claiming potential detection of contract cheating. Meanwhile, there is some press interest in a Danish system, ghostwriter. Details of this are published in a preliminary report.

The administration of detection

The increasingly digitised nature of university assessment procedures makes it likely that some of the automatic detection methods described here will be widely adopted soon. This may create new forms of synergy between administrators (who often manage these systems) and academics (who assess the work submitted to them). However, an increased rate of offence suspicion (and perhaps detection) might also mean more staff stress associated from the actions that follow up such a flow of cases.

Vehvllainen et al (2018) have considered the job resources staff will need to aid them in coping with these demands as faced in the context of a network of intertwining communities (scholarly, pedagogical and administrative). To explore this, 18 teachers from two universities were interviewed about the resources required and the stresses that arise around academic integrity management. They identified these challenges:

- Rupture in the personal pedagogical relationship,

- Challenge on the supervisory “gatekeeping” responsibility;

- A breach of the “everyday normality”;

- Ambivalence in explaining plagiarism and

- The strain of performing the act of accusation

They note how teachers must balance both rule-ethical and care-ethical orientations in their practices. The job resources they identified as helpful for this were:

- Conversations with colleagues and other reflective spaces

- Support from superiors and administrative personnel

- Shared playing rules, procedures and plagiarism-detection programmes

At some point detection has to move to confirmation. There is relatively little shared wisdom and experience around how best to engage with students under such circumstances. Hopefully more institutions will publish guidelines on managing these conversations – here is one example and here is another.

In sum, as with text plagiarism, it is likely that automated processes will become increasingly important in the detection of social plagiarism. However, this detection will never be perfect, and managing the processes will continue to be a point of stress for many colleagues. Moreover, automated systems may serve to draw a wider range of job families into the monitoring, detection and disciplining processes.