A recurring theme in these pages has been uncertainty of the boundary between good learning practices and offences against academic integrity. Students often have difficulty navigating this space, and institutions can be poor at guiding them with regulations. In part this is because the good/bad boundary is inherently unstable: amongst other de-stabilising forces, it can be challenged by changing ideas regarding the psychology of teaching and learning. Shifting theories about how human beings best learn may not always fit well with prevailing regulations about proper study practices. Yet many students will subscribe to such theories – even if only implicitly understood. They are theories whose propagation is often only gradual: discretely finding their way out of Schools of Education or Psychology, into programmes of teacher education until, finally, they are encountered by students as educational practice. The significant point is that students who are aware of such theories (perhaps implicitly) will construct from them their own understanding about how best to act.

In this section, we highlight two current directions in theorising around human cognition and learning, suggesting that both are potentially provocative for how institutions frame integrity regulations. These ideas concern what it is to claim knowledge, and what it is to impart it. They both invoke the notion of ‘mediation’.

The mediated nature of human experience is often the basis for distinguishing ourselves from other animals – with their im-mediate experience of the world. Human beings typically realise their goals indirectly, through the mediation of tools. These tools can be material in nature or they can be symbolic (language, mathematics etc). The social nature of the world becomes significant when we are learning – i.e., still acquiring confidence in these mediational practices. Other peoples’ engagements with learners will support the progress that those learners can make.

The ‘extended’ mind

Most everyday understanding of human intelligence invokes a robust in-the-head (or perhaps in-the-brain) model of knowledge and knowing. Meanwhile, current psychological theory tends to stress the ‘distributed’ nature of intelligence: knowledge is an integration of things in the head with things in the world. Those worldly things include tools, rituals, environmental designs.

Gregory Bateson (1973) captures this in asking: “Suppose I am a blind man, and I use a stick. I go tap, tap, tap. Where do I start? Is my mental system bounded at the handle of the stick? Is it bounded by my skin? [etc.]”. Contemplating the same uncertainty, Andy Clark coins the phrase “extended mind” to express an integration of the (privately) mental with the (externally) material. His own example involves an elderly person with failing memory (Otto) and a younger friend (Inga). They both visit a museum. Otto manages a route through the exhibition with a set of written notes. Inga recalls it from previous visits. So they both use memory. Why should our account of Otto’s memory be any different from our account of Ingas? This perspective is accessibly developed in interviews Clark has made with the New Yorker and with the Institute of Art and Ideas.

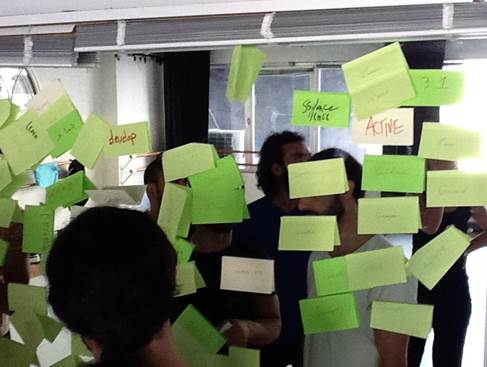

In these terms, a piece of paper can be a modest extension of the mind. The mind map or concept map (Davies, 2010) offers a slightly more elaborate example. Or, going further, post-it notes could similarly do ‘cognitive work’ – if a task made it important to coordinate with other people. However, personal digital technologies create a real wealth of such examples – particularly in relation to memory. In a much-cited study, Sparrow et al (2011) demonstrate not simply that people extensively use computers to retain information but they are more likely to forget information stored in this way. What they remember is indexical – namely, the fact that they have stored it for use when needed.

Students certainly may not conceive of their relationship with tools in terms of deep theory. Nevertheless, across education they will have acquired an intuitive sense of technologies as ‘tools of thinking’ or ‘tools in thinking’. Creative problem-solving draws upon such resources as personal notes, downloaded papers, and social messages. Increasingly, these are curated in the single medium of a personal digital device. A dynamic workspace of this kind may not be naturally partitioned into resources that demand citations and those that do not. Such conceptions complicate what it is to ‘know something’ and, therefore, can blur boundaries that relate to ownership and authority.

The social character of learning

Current educational theory also stresses the social nature of learning. This may seem an unexceptional emphasis. It is surely obvious that other people are important to our learning – not least as teachers. However, while traditional theory certainly acknowledges teachers, parents, peers etc, it tends to position such social agents more as facilitators of learning. They merely orchestrate activities, thereby empowering learners themselves to act productively. While more current theory stresses the importance of processes that are intrinsic to those interactions that take place between a learner and other people.

Typically, four such social-interactional processes are invoked. (1) Productive conflict: whereby a learner, through social interaction, encounters a perspective contrasting with their own. Within such conflict they may experience pressure towards insights that allow a reconstruction of their own perspective. (2) Internalisation: whereby a more knowledgeable partner, in socially scaffolding some shared problem-solving episode, makes moves (in action or speech) that can be internalised by the learner as future resources. (3)Reflection: whereby conversational pressure may more readily facilitate meta-cognition – or a n active and critical engagement with one’s own thinking strategies. (4) Community: whereby participation in the coordinated problem-solving of social groups both enables the witnessing of strategic thinking as well as promoting a motivating sense of identity in relation to the focal concerns of such communities.

Such theory may be registered (implicitly or explicitly) as one basis for working on assignments closely with other people. But there are other messages that may encourage the same socialising study strategy. One would be an awareness that employers are frequently emphasising the importance of graduates needing skills of collaborating (CBI, 2009). Another might be the way in which university prospectuses celebrate students working together when depicting study in promotional images. Still another would be an awareness that in many of their university courses group projects and group assignments are well-established modes of assessment.

Whatever its origins (grand theories or otherwise), students will increasingly be oriented to a personal model of learning whereby one’s own actions and beliefs are enmeshed with the actions and beliefs of others. Our own research conversations in focus groups, the free comments on our survey returns, plus a wealth of literature together builds a clear message on this topic. Not every student welcomes group projects for assessment – although many do – but most will regard collaborative relationships during study as precious. Indeed they are often confused and irritated if such relationships seem to be proscribed.