It may feel impossible to speak of “colluding with a machine”. And yet there is a growing family of digital tools that offer help in the completion of intellectually demanding tasks. Such tasks might include university assignments. The examples discussed on this page are therefore marginal to our overarching topic of ‘social plagiarism’ – although it is “IA” (intelligent assistants) rather than AI that is discussed with concern among language practitioners (e.g., Kukulska-Hulme, 2019). However, the reach of artificial intelligence into various arenas of human-machine communication is now widely discussed. There is some reason to suppose it may reach into those conversations that can lie behind the production of a university assignment.

Intelligent topic research

There are many ways in which a digital device can support student cheating – this site ‘helpfully’ assembles 10 possibilities. However, one approach that resonates with our concern here with social help-seeking is a service that provides a ‘personal assistant’ for online researching of an assignment topic. This may take the fairly simple form of a service such as slader – a website that invites questions and then searches online textbooks for possible answers. Such services work most effectively for those computations that might form part of assignments in mathematics or engineering. However, a more ambitious project is Wolfram Alpha. Which, in an explanatory TED talk, its founder refers to as a ‘computational knowledge engine’. Again, it may be quite successful with relatively self-contained information enquiries. However, and by way of example, asking it to deal with a more abstract case – such as “Samuel Johnson’s relationship with women” is less impressive. It generates nothing on the Enlightenment scholar but, instead, some data on the American businessman Samuel Curtis Johnson, Jr. This seems, therefore, a singularly un-intelligent service.

Many such websites rely on a fairly crude searching of Wikipedia and other online resources. For instance, the Samuel Johnson title, when entered into EssaySoft (an AI essay generator), provided text that started:

This would hardly be a suitable way to start an essay on the topic and parts of the text are simply lifted from brittania.com. However, reference to Hester Thrale is surely central to what any essay would address and so patching paragraphs together and testing it on a local Turnitin could nevertheless offer a useful service to the rushed student.

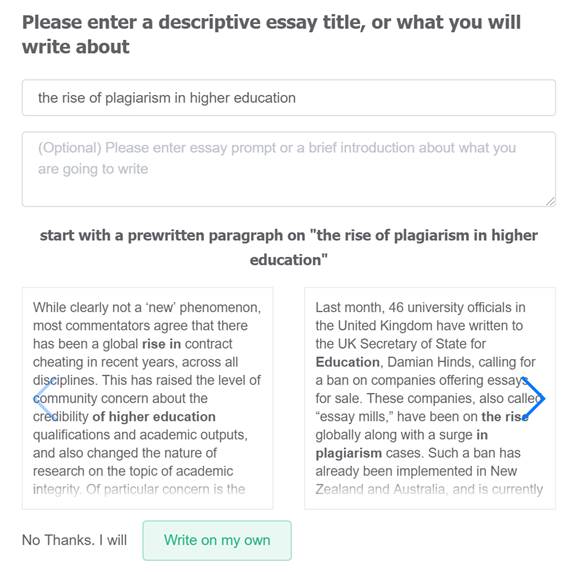

On the other hand, the service essaybot seems rather more helpful in its approach to borrowed text. For a requested topic it offers a starting paragraph which can be treated with internal tools that alter the grammar and vocabulary of the text to make it less like the source from which it came. Consider the example below:

A number of paragraphs are offered as potential starting points for the proposed essay. Moreover, once an opening paragraph has been chosen, then the service offers a variety of follow-on paragraphs that might be added. Again, internal restructuring of sentences by site software is possible, although the user may elect to do this themselves. The constructed essay is usefully shown developing within an in-site word processor on the left of the screenshot below. This encourages customers to refine the text through editing:

Intelligent paraphrasing, patchwriting and translating

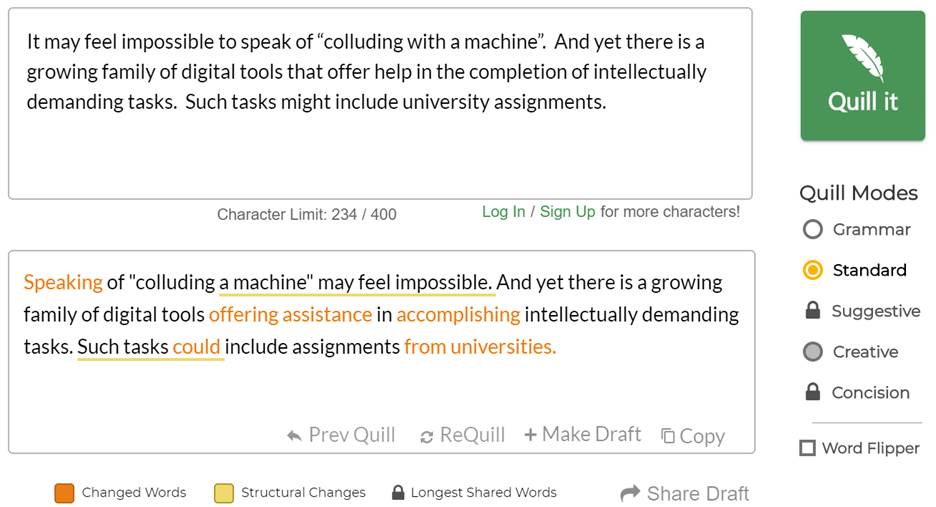

As discussed above, text from elsewhere that has been cut and then pasted into an assignment may escape detection by institutional software if the student first alters aspects of its grammar, structure and vocabulary. However, this is a practice that also can be automated online. Sites such as ‘Paraphrasing-tool’ and ‘prepostseo’ will effect such editing. To illustrate: the two opening sentences of this present webpage were entered into the service Quillbot:

The tool is generous in highlighting the nature of the changes it makes. They seem to generate a text not greatly changed in meaning but, perhaps, more resistant to plagiarism-detecting software. At least, a student self-testing their text on a plagiarism detector will discover for themselves if they have done enough.

However, the form of online text massaging that may be most powerful is that which translates between languages. There is growing evidence that google translate (possibly the most widely used) can perform very well compared to human translation (e.g., Aslerasouli, P., & Abbasian, 2015). This is a challenge for language courses within which there are assessments based on translation. As Correa (2014) points out “instructors find themselves playing ‘forensic linguist’ in order to gather evidence of cheating”. While Kim and LaBianca (2018) report widespread and unhelpful variation in attitudes towards such tools, as manifest by a large sample of students and faculty at one US university.

Intelligent calculation

Generating meaning in text and doing so though interactions that allow personalising of requirements is an ambitious aim for artificial intelligence. More realistic goals can be sought with the more traditional computational tasks of mathematics and engineering. To such ends the smartphone app ‘photomath’ offers solutions to complex equations, even when they are photographed in handwritten form. Human intelligence can be combined with the artificial by allowing the smartphone to photograph an assignment problem and then act as the medium whereby it is communicated to a human tutor for help. HWpic is an app that achieves this, noting that: “All tutors are graduates from top Universities such as UCLA & USC”.

The realistic future of artificial intelligence for assignment cheating is likely to be ‘blended’ versions of help similar to this illustration. On this model, digital tools can generate text or capture problems, while the personal device then also acts to recruit external human help for completing what is required by the assignment.