Not all learning tasks can be completed by students working alone. In such circumstances, seeking help is a rational strategy – certainly better than giving up too quickly or doggedly persisting with frustration. What we are calling here ‘help seeking’ might sometimes be more simply termed ‘research’ – at least when it implies a student finding relevant digital or print sources and then exploring them for direction. Although when such inquiry is pursued in libraries, some students can still be impeded by lack of confidence – experiencing what is sometimes termed ‘library anxiety’ (McPherson, 2015). Sadly, many students are found to be poorly equipped with versatile search strategies and this may not be easily influenced by training (Weber et al, 2019). Whether conducted in libraries or on the internet, studies have highlighted the conservative nature of student search when seeking help from such sources. Simply put, they are reluctant to go beyond well-tried strategies that are often limited in power (Connaway, 2011; Warwick et al 2009).

Help seeking of this ‘in-the-library’ variety has typically been researched with students in the later years of education. While during the school years, seeking help has been considered a more social practice – turning to other people for support, notably teachers but also peers. Some studies suggest that the form it takes can reflect the influence of prevailing classroom climates, as created by teachers (Shim et al 2013). These studies then highlight the fostering of help seeking that is ‘adaptive’, i.e. those actions that are well matched to a point of need. Otherwise, help seeking may be expedient (simply soliciting ‘right answers’) or dependent (less demanding but triggered immediately any difficulty is encountered) or avoidant (never pursued, even when needed).

However, while such categories may offer useful distinctions, they tend to encourage a ‘trait’ conception of help seeking. In this way it is framed as a fixed disposition of individuals, rather than a more fluid practice, shaped and changed by contexts. Some research indicates that relatively ‘adaptive’ approaches to help seeking are present even early in the preschool years (Vredenburgh and Kushnir, 2016). This might imply that, at the outset, children possess a default strategy for productive help in problem solving, i.e., one that will usually be in the best interests of learning. Other, less effective, approaches may be a consequence of various socio-cultural forces/pressures that can arise within formal schooling. Universities are evidently one such context. In the next section we consider how study in higher education is often embedded in social relations.

Socialising university study

Educational theory acknowledges that getting help should be central to any definition of the term ‘studying’. Yet our intuitions about this term may too easily suggest it refers to a somewhat private form of information searching – typically in libraries or on the internet. So, our conception of ‘help’ is that which students can obtain as a result of self-contained effort or agency: the results of a strategic but private interrogation of available published sources. For example, at the time or writing, if “studying” is typed into Google images, the first 12 hits very much reinforce this idea (see below). Perhaps Google images is a rather rough way of fixing concept meanings but, nevertheless, the results surely resonate with intuitions. So, this montage idealises studying as: first, a practice characteristic of the university years; second, one that demands abstraction from existing sources; and, finally, an experience that demands a somewhat solitary discipline.

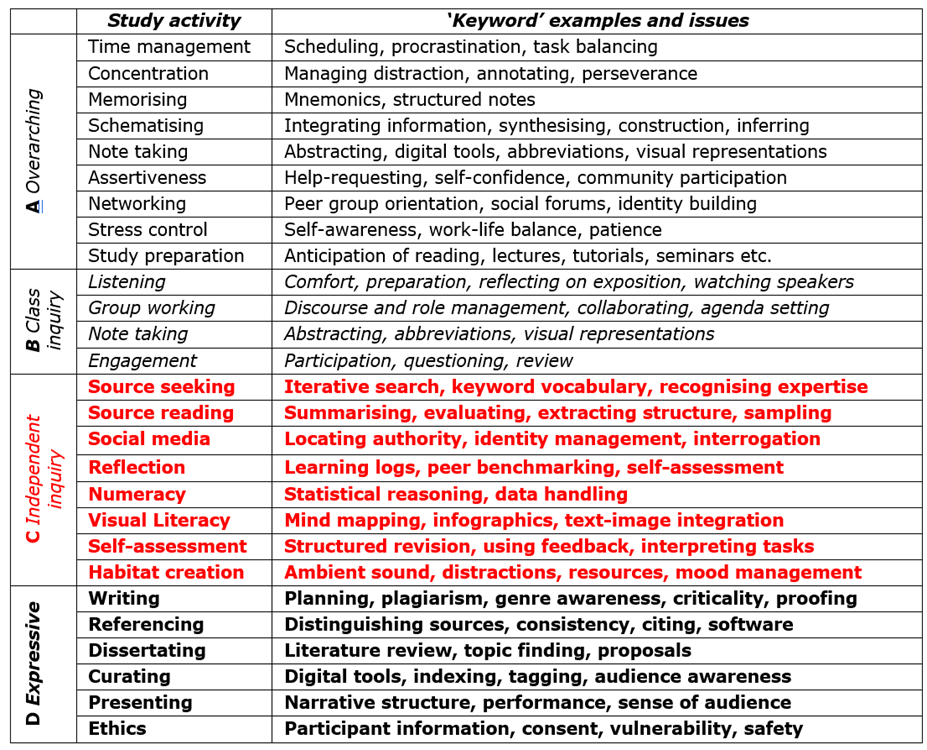

Try the same exercise with the word “learning”. The results are telling: the connotations of ‘learning’ suggest a mental or ‘in-the-head’ concept, while ‘studying’ was rendered in images as a more practical engagement: acting ‘in-the-world’ (particularly with texts). However, a moment’s reflection will suggest that the repertoire of those activities mobilised for the practice of study is much broader than that depicted in the pictures above. The following table is one possible inventory of a more inclusive set.

While some of these activities seem exercises of private mental agency, most will involve acting-in-the world and many of them can be pursued in a coordination with one or more other people. This is the reality of studying as a heterogeneous and worldly activity: it’s many features will be pursued socially. Study is not best understood as practices that are exclusively either in-the-text or an in-the-head, but practices that can depend on the dialogues of social life.

The image of a solitary student might have fitted more comfortably when assessment of study was through unseen, closed-book, closed-door examinations. But, as Richardson (2015) has documented, universities have shifted away from this model and moved towards continuous or ‘coursework’ assessment. There are many reasons thy this move was attractive – and Richardson lists them. But one consequence has been that it renders study a more shared experience, as students often find themselves working on common or similar projects, in extended time and across shared study spaces. Thus, it seems natural for a student to seek help from others, given this awareness of their peers as engaged with shared projects and shared deadlines. Help seeking thereby becomes a more socially mediated practice. Moreover, the growth of internet services for communication greatly increases the ease of that mediation, and the range of what may be trafficked through it.

Social help as collaboration, or collusion

Unfortunately, while the provision of such help (or the seeking of it) can be a precious social commodity in most circumstances of learning, in some others it can be forbidden. The most troubling circumstances are those where it is individual competence that is being judged – by so-called ‘summative assessment’ (Knight, 2002). Conflicting perspectives on the propriety of certain help seeking around such assessment may then create tensions. Students and tutors may hold perspectives on ‘help’ that are genuinely but innocently different. Moreover, trouble may be further amplified when one party decides to question the other’s sincerity.

We have reviewed guidelines set down by universities to cover proper practice in situations of such assessment (Crook and Nixon, 2019). Often, advice would proscribe against seeking help from other students when an assignment was to be summatively assessed. We argued that such policies fit poorly the typical conditions of study. Learning collaboratively with peers would be commonly encouraged and yet, at the same time, it is urged that discussion of matters relating to a coursework assignment should be cordoned off. The student is thereby left uncertain as to the boundary between collaboration and collusion (Barrett & Cox, 2005; Sutherland-Smith, 2013)

We expressed this tension as follows: The terms of collusion guidelines are troublesome when their demands do not cohere well with how a curriculum is presented or with its expected study practices. Summative assignments are often set early: perhaps they are declared in a course handbook distributed at the outset. There then follows a journey of study. Reading and listening episodes get organised. Writing and reporting tasks must be executed. Perhaps computations have to be performed or artefacts constructed. On such a trajectory, it may not be clear to the student when preparation for the assignment starts. It is fanciful to suppose that some assessed piece of exposition has, once set, a distinct moment when the work is initiated (and collaboration around the topic must stop).

This situation may have unwelcome consequences. One consequence might be an innocent confusion about the collaboration/collusion boundary for help seeking and this may lead to unexpected disciplinary procedures. On the other hand, students may be more irritated than confused by collaboration proscriptions. Lack of faith in institutional regulations does not help foster academic integrity.

The variety of relationships in help seeking

If regulations governing academic integrity in assessment are inconsistent or irrational, this becomes an unhealthy situation. Students may be genuinely uncertain as to practices that they should not follow. Or they may become disrespectful of regulations that don’t seem to make sense. However, careless regulation is hardly the only basis for violations of academic integrity. Study now takes place under conditions that can furnish a variety of stresses. So much so that students may knowingly violate proper practice – perhaps having to balance conflicting emotions, motives and aspirations. Accordingly the sections that follow consider the range of ways in which the threshold for social plagiarism may be lowered.