Student cheating is a topic sometimes addressed in the literature of criminology. Perhaps an understanding of what motivates violating the law of the land might also help us understand what motivates violation of academic integrity. However, asking why someone commits a crime is a question that can be answered in different ways. For those whose job it is to make crime less likely to occur, some ways of analysing its causes are more compelling than others. This equally applies to ‘crimes’ of student cheating.

We consider here the principal ways in which causes of offences such as social plagiarism have been analysed. Put simply, explanations can take an inside-out or an outside-in approach. They differ in terms of where the weight of causal explaining is placed: inside or outside the actor. The former highlights factors within. It starts by evaluating aspects of the individual’s disposition or identity, and then determines if these predict a tendency to offend. While the outside-in approach starts from evaluating circumstances in the environment, considering whether their presence predicts offences being more likely. However, note that a common outside/in assumption is that the way such ‘outside’ forces exert their influence is by shaping the ‘inside’ motivations or attitudes of community members (although outside-in approaches may not always actively theorise what those specific inside factors actually were).

Inside-out explanations

For example, in a systematic literature review seeking to clarify the psychological causes of plagiarism, Moss et al (2018) highlight findings that stress offender ‘types’. Plagiarism is more often associated with such personal characteristics as impaired resilience, limited confidence, impulsive tendencies, and biased cognition. Some criminologists question the value of explanatory systems based upon criminal ‘types’ or criminal ‘careers’ (Gibbons, 1988). Certainly, in the case of academic integrity, it is not clear how such typologies help institutions in their practical task of limiting the occurrence of such offences.

Outside-in explanations

However, explanations that start from the context rather than the person, can present institutions with similarly intractable problems. For example, institutions can do little to influence cultural forces such as students’ experiencing an overbearing pressure to succeed in a competitive and expensive education system – the kind of causal dynamic criminologists address through ‘strain’ theorising (Smith et al, 2013).

The problem with that sort of example – as with inside-out dispositional examples – is that such causal accounts can leave institutions relatively helpless in repairing the problem. An individual’s psychological profile is not easily recalibrated. Neither is it easy for institutions to counter the oppressive impact on student experience of prevailing cultural or political forces.

However, ‘outside’ factors that encourage offending do not only arise from within the overarching culture in which education is embedded. Institutions themselves create cultures. Therefore, research could scrutinise these local academic contexts, classifying and quantifying their character. Such description could then be co-related to the occurrence of academic offences and, finally, any ‘risk factors’ identified might be dealt with. Moreover, such findings may turn out to generalise and so be applicable across institutions. This is a viable approach although often less revealing that expected. Mainly because factors in any complex cultural setting may not act in a direct or mechanical fashion. Their influence may arise from their ‘chemistry’ – the interactions between them. So quite sophisticated statistical modelling of such interdependencies can therefore be required.

Students explaining themselves: ‘normalisation’

Both approaches sketched above explore why students offend by systematising the variables supposedly implicated: that is, factors emanating from either ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the individual. Researchers will often strive for objectivity or detachment in this effort. However, this may constrain their interpretations. Because actors, events and environments may not be understood in the same way by students as they are perceived, measured and classified by researchers looking on. Therefore, the most useful approach may be to consider how offending students do report understanding their context and how they interpret their own actions within it.

So, when challenged on an offence such as social plagiarism, what sense-making can students invoke? One approach towards justifying a claimed offence is by supposing that it has, elsewhere, become normalised action – as in the familiar appeal: ‘but everybody’s doing it’. For example, Rettinger and Kramer (2009) found from surveys and from responses to integrity vignettes that “observing others cheating was strongly correlated with one’s own cheating behaviors.” That is, some students were judging cheating as ‘normal’ – and thereby acceptable – because it was witnessed as widespread in their own community.

Evidently, institutions can confront this by attempting to control the scale of visible offending in their communities. However, examples have been given in these pages of normalising forces that are less easy to influence or accommodate. This is because they exist in that wider culture beyond the institutional community. Ghostwriting is an example: it might be viewed as a kind of social plagiarism. Yet its acceptability and ubiquity suggest a culturally legitimate practice, thereby rendering assignment outsourcing ‘normal’ or respectable. Other cultural practices will normalise social plagiarism in more subtle or indirect ways. We have identified some of them elsewhere on these pages. For instance: the forces of commodification, the fluid nature of exchanges in digital media, and the ‘learning-is-social’ imperative from educational theory. Students’ awareness of these developments as ‘normal’ in the wider culture may lower the threshold for contemplating a practice like social plagiarism. Because they are trends that seem to complement or overlap it.

While such justifying-through-normalisation may underpin some integrity offences, it may not always be a process explicitly recognised or articulated by those offending. Indeed, these examples may belong to a whole family of cultural trends whose influence rarely prompts conscious reflection. It may be for social science to highlight these possible associations and, then, for integrity managers to consider how they can deflect their influence.

Normalisation arises from reading the context and judging that your apparently offending practice actually conforms to what others are doing. While neutralisation arises from reading the context and judging that the context is flawed in ways that warrant the apparently offending practice.

Students explaining themselves: ‘neutralisation’

If there are rationalisations for integrity offences that do enter conscious reflection, students may not wish to self-report such matters to researchers. Amigud and Lancaster (2019) worked around this embarrassment by classifying the reasoning revealed by student customers within their purchasing messages placed on ten contract cheating websites. Five ways of explaining the need to purchase help were given: (my) academic aptitude, perseverance, personal issues, competing objectives, and self-discipline. However, because students were addressing contract authors unaware of that students’ institutional context, these reflections may have favoured a strong inside-out rationalising; focussing on constraints of personal character or circumstance. In other words, explanations that may still risk leaving institutions stranded confronting a gloomy determinism of personality types and traits.

If a valid method of questioning could be found, students’ attempts to make sense of their offending actions might be more revealing. Particularly those rationalisations where offenders admit their actions were wrong, but they still respect the moral code that was violated. Understanding this position can help institutional regulators, because rationalisations are often constructed from something felt as troublesome about the particular situation in which the offender acted. Rationalising will typically invoke ‘local’ features of the educational environment – forces that somehow overwhelmed the moral code. Institutions could then hope to reconfigure those circumstances.

It is this pattern of reasoning that has come to be described by criminologists as ‘neutralisation’. This derives from a theory proposed by Sykes and Matza (1957) to systematise the rationalisations of criminal offenders. Neutralising was expressed in terms of five justifying moves offenders might commonly make.

- Denial of responsibility: it was accidental. Or forces were beyond personal control

- Denial of injury: yes, freely chosen but no one was harmed

- Denial of victim: those suffering deserved it or asked for it

- Condemnation of the condemner: real moral lapse resides in those who accuse

- Appeal to higher loyalties: offending act was consistent with other, higher moral responsibilities

This taxonomy has been successfully applied to cases of secondary school cheating (Zito and McQuillan, 2010), but also to undergraduates. LaBeff et al (1990) found students’ sense-making of their offences fitted three of the above categories. The most common was #1, then #4 and then #5. Condemning in #4 was directed at various shortcomings in the educational provision. While the higher loyalties students invoked were those that other researchers identify (e.g. Ashworth et al, 1997) – namely, friendship, interpersonal trust and effective learning. It does seem that #2 and #3 from this list could be less likely, although McCabe (1992) has reported occasional cases of both.

Loss of agency in assessment

Research exploring such student reasoning often uses survey methods. Surveys tend to assume that researcher and informant share the same framework for understanding the issue. Therefore, release from this constraint might be sought through interviews or focus groups. These allow for negotiation of understandings and thus may give greater confidence when interpreting participant offences. Unfortunately, those methods typically mean participant samples must be small. Moreover, a necessary ‘focus’ (say, on assignment offences), coupled with felt pressure to contribute, may prompt participants to invent perspectives or explanations.

A still more usefully indirect way of exploring causal processes is to seek students’ critical reflection on their experience of doing assignments – with no prompting reference to possible offences. Because it is tension or disturbance within those experiences that creates the conditions that tempt violation of regulations. In neutralisation terms, such troublesome experiences provide the raw material for #4 above – that is, the condemnations of those very individuals (institutional managers or assignment tutors) that condemn the students’ offence.

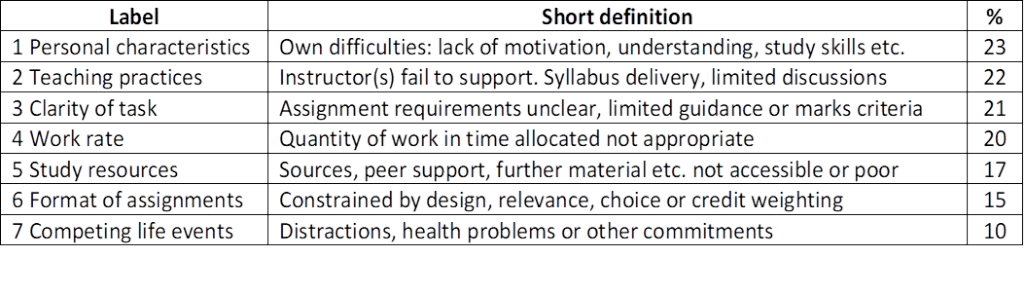

In our own research we issued a survey to students at two universities (see our page on ‘methods’): it included invitations to make (anonymous) free text comments on recent assignment experience. 811 students made such comments and, on analysing these, we reliably detected the following seven themes (ranked here in order of the percentage of that sample that referred to each).

The Table provides a short definition for each thematic label. It is sobering that the issues raised by students in these free text comments went beyond those we designed ourselves in ‘strongly agree / strongly disagree’ questionnaire formats. This reinforces the case for not assuming an overlap in student/researcher perspectives. Taken as a whole, the comments that underpin these categories reflect what Harris et al (2018) refer to as a “loss of agency” on the part of students. We infer that, in some cases, this becomes a stressful predicament and one that can lead to violating assessment expectations. As Harris et al express it: student behaviour becomes more ego-protective than growth-oriented.

A loss of agency could be expressed in relation to personal ‘inside’ factors – such as those exemplified by #1 above, that is cognitive or motivational shortcomings, or in relation to personal ‘outside’ factors, such as illustrated by #7. Many comments raised in #2 – #6 referred to familiar perceived shortcomings in course delivery. They echoed examples solicited by Beasley (2014) to a survey item questioning “What would have stopped you…” – students deflecting blame for their misdeed towards teaching and resource. It may be unexpected that such a large number of comments were made but perhaps it is striking that they were often made very firmly.

Poor/useless feedback, lack of direction, not being told exactly what we were doing. We had an hour long lecture on our coursework and throughout the whole thing they never actually told us what we were doing for our coursework. When we were eventually told it was a literature review it was just assumed that we knew what a literature review was.

Often we were given only about a week or so to do some quite difficult assignments. This would have been manageable if we didn’t also have a few other assignments from other modules due in around the same time. Perhaps module organisers could talk to each other and try to plan to space deadlines apart or give us more time if we have a lot due in at the same time, because we often simply don’t have enough time to do everything to the best of our ability, especially if we would like not to be working every waking hour of the day.

I don’t always find tutors approachable and when I have they often seem dismissive so consequently I tend not to ask and try to find my own solutions.

21% of the 811 students making comments referred to an issue of understanding what they were expected to do in an assignment (#3). This is a less frequently acknowledged problem but was one often forcefully expressed. Therefore, it illustrated the very kind of frustration, sense of victimhood, and loss of agency that might easily neutralise an integrity offence.

Vague instructions leaving you unsure of what was required of your coursework piece.

There was no advice to what a university-level essay should look like. Throughout all my coursework except creative writing, I was really unsure what was expected and how it differed from A Level.

When the assignment details were confusing, or the tutor was not able to explain the details of the task with enough clarity.

Understanding exactly what was required and ensuring I had met the brief, as opposed to working hard but not quite doing what the coursework required.

In this project, comments of the kind shared in our survey coupled with focus group conversations have highlighted two themes that feel significant for shaping integrity offences. The first is recurring reference to the importance of fairness. The second is the possibility of being felt a ‘victim’ of assignment design or practice. While students might freely endorse the need for integrity regulations and even welcome the form that they take, they represent only one moral code that students might feel obligations towards. Therefore, in understanding and repairing the conditions for offending, this tension between moral codes deserves to be recognised.