Un-contracted help seeking

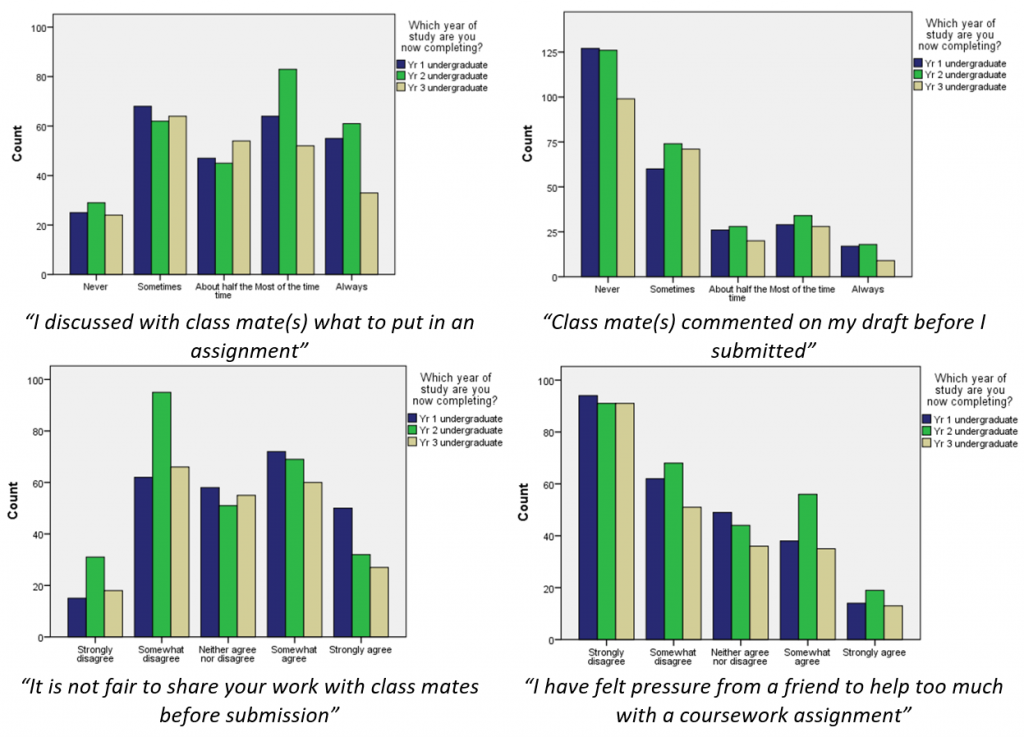

In discussing social plagiarism, we have distinguished those cases that have a commercial (or contracted) dimension and those that occur more informally. The latter would include help that is sought from student peers and from family. It is not possible to comment on the scale of the latter, as no studies have explored this. In our own research we find some indication of its prevalence. Students were asked Likert-style questions concerning both behaviour and attitude in relation to working together. Four sets of responses are shown below for undergraduates in years 1, 2 and 3. The questions asked are shown underneath each figure.

The top left figure suggests collaborative discussion of assignment content is commonplace: more respondents agree they do this. While the top right figure implies there is less discussion, perhaps occurring later, around drafts. On the other hand, lower left suggests that this is not simply because doing so is thought unfair: low frequency of commenting on final drafts is complemented with relatively high frequency of believing its OK to do so. Thus that low frequency of actual draft discussion is more likely to reflect time pressure of deadlines. Finally, the lower right figure reinforces the idea that informal help with assignments is quite common – by highlighting how some of the time it can be unwelcome.

Contracted help seeking

Within the commercial, or contracted, space of outsourcing assignment work, there is a better chance of estimating scale of practice because of the more public and accountable nature of the commerce. Statistics from disciplinary bodies in higher education might be one source of estimates. However, although the press have been active in noting the evidence that cheating – and plagiarism in particular – is increasing, the offence of outsourcing is much more difficult for institutions to detect and thereby estimate as a problem. Perhaps it assumed to be infrequent. The shadowy nature of this practice may mean that suspicions are more reluctantly followed up. Evidencing the scale of provision can only be confidently pursued for conventional essay mills – while freelancers are readily found advertising online, there is little known about their numbers or how must business they attract.

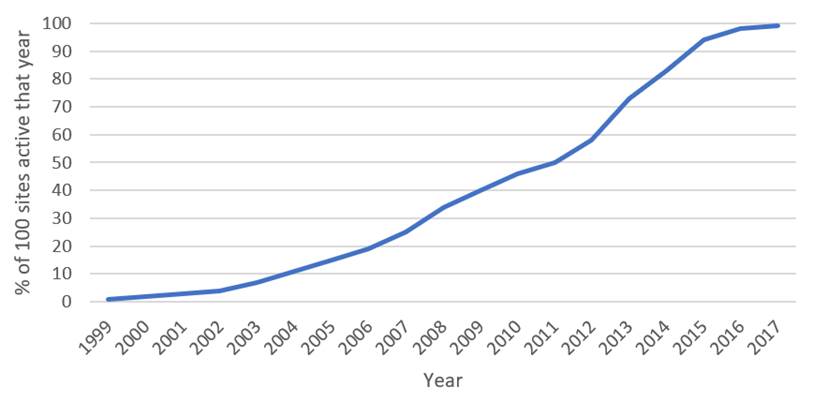

Certainly, the mill sites are thriving. Ghostwriter David Tomar lists 325 in his essay on the industry methods; the Kimbel library has documented even more. However, extended lists may imply high activity but only in the most general terms. Many differently named sites feed into the same master site. Simple longevity might be a useful measure of buoyant business. In our sample of 100 sites, we used the internet archive to determine how long each site had been active online. The graph below indicates that 50% of the 100 were active 8 years ago in 2011. This suggests a relatively stable and prospering industry.

The morally dubious nature of contracted outsourcing makes it difficult to find formal records of business activity to help estimate the scale of this industry. However, one company (Assignments4U) have had their trade made more visible through the records of a cheating court case in New Zealand. The scale of this company’s income was considerable: between 2006 and 2013 total profits were $4.6m, with an average assignment costing $406.

Owings and Nelson (2014) have reached a similar conclusion regarding scale of profit from research that scrutinised the dashboard records of two case study sites (BestEssays.com and customwritingservice.com). In a close and convincing analysis of reported assignment traffic they estimated annual revenues of $12.3m. If these two businesses were typical, they estimate that “the overall industry would have revenues of $3 billion”. Ownings and Nelson admit this is likely to be an over-estimate; nevertheless, the case study income figures do suggest assignment outsourcing exists on a large scale.

Extent of student use

Investigations of students using outsourcing services do not make distinctions between trade within different sectors of education. Universities might therefore be most interested in statistics that refer only to higher education and, ideally, statistics that estimate the extent to which their students are using these services. There are two approaches to this problem. They both involve simply asking (anonymously of course) students to declare their involvement – or their likely intentions.

The fist method of student inquiry involves surveys of students. There have been many of these. Yet their results may erroneously be related to outsourcing assignments because the questioning is too vague. For example McCabe (2005) reports results showing that 7% of undergraduates and 3% of postgraduates submitted “work done by another person” – which may count as ‘social plagiarism’ but is too vague to capture paid outsourcing.

In a paper widely reported in the media, Newton (2018) has carried out a systematic analysis of published research that surveys self-reported cheating by undergraduate students. His paper focusses on those studies that specifically questioned whether a respondent had ever paid for an assignment. Newton finds 65 useful studies; together they involve over 54,000 students. He plots trends in reported contract cheating across the period 1978-2016.

The finding most frequently reported in the media is that in the period since 2014, surveys report an average of 15.7% of those students surveyed admitted to having paid someone else to undertake assignment work. Over the entire period the average is much lower (3.52%), but this reflects a rising trend across the period in terms of how many students are reporting the practice. Newton dwells on various reasons for this increase but does not give close attention to what may be a major influence on historical trends: namely, the growth of digital tools, networking infrastructure and the ease of user access to these. Together these developments surely make this business such a very comfortable fit to the internet.

Earlier studies had reported lower levels of use. For example, Scanlon and Neumann (2002) surveyed 698 students on nine US campuses and report 6.8% had “sometimes” and 2.8% “often/very frequently” purchased a paper. It may be conjectured that spreading access to the internet has made the trade in this ghostwriting more buoyant.

Newton’s sampling sought surveys in which student participants answered “yes” to a question about whether they “had purchased, or in some other way paid money for an assignment” (some sampled surveys said only “purchased or obtained”). Therefore these responses may include freelancing authors. Fewer recent studies have been more direct in citing essay mills in particular as the source of a purchase. In a 2014 survey of 106 undergraduates at a US university, Curtis and Vardanega (2016) find 2.8% admitted to purchasing work from an online site. Yet this is small sample and there must be some chance that the 3 students who affirmed this action did so frivolously. However, Curtis and Clare (2017) integrated results from five US studies that had used the same assignment-purchasing survey questions and found that 3.5% to 7.9% of undergraduate responding reported purchasing. These are lower than Newton’s 15.7% estimate but his net may have included freelancers and that statistic refers only to very recent years.

A second approach to estimating student vulnerability to social plagiarism is simulation. A rare study of this kind is reported by Rigby et al (2015): it refers only to buying essays from contract cheating websites and willingness to do so. A sample of 90 second year undergraduates from three universities were invited to indicate willingness to purchase in relation to a (real) essay that was shortly due. Decisions were made anonymously and privately in a simulation environment. Various levels of incentive and risk were offered. Women were more risk averse than men. While students who were less risk averse and students who had English as a second language were more likely to say they would purchase. Half of the sample opted to buy under at least one set of choice conditions. The authors conclude: “We consider it remarkable how many students, in a study administered by academics, indicate a willingness to buy. The assurances of confidentiality were genuine but the level of purchasing indicated was contrary to the expectations of both the authors and their colleagues.”