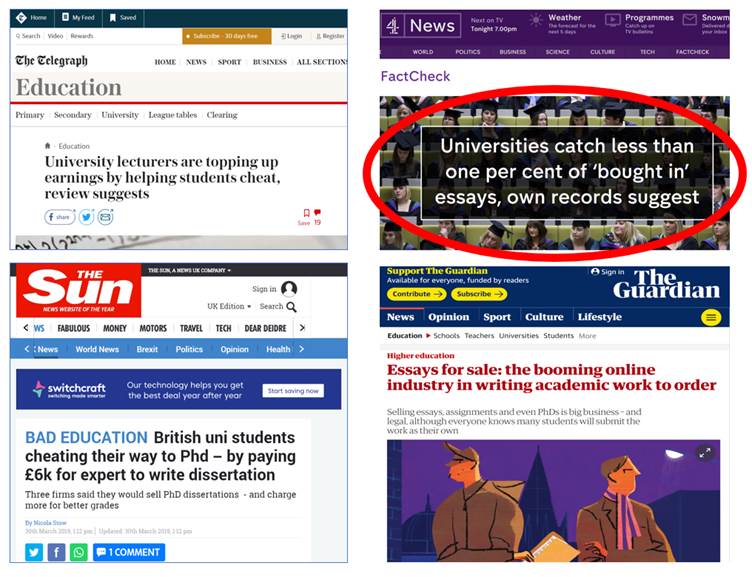

Universities strive to protect and promote principles of academic integrity. Among violations requiring regular management are those whereby students falsely claim ownership of submitted work. Often, such circumstances are contested, difficult to judge, and require investigative meetings that are stressful. Many onlookers – students, staff, parents, politicians, journalists – comment on this situation with dismay. Arguably, there is a ‘crisis’ of management surrounding this form of integrity lapse. Whether crisis talk is justified by the absolute frequency of offences might be debatable, but justification can certainly be found in the awkward visibility of the problem and the apparent failure to address it.

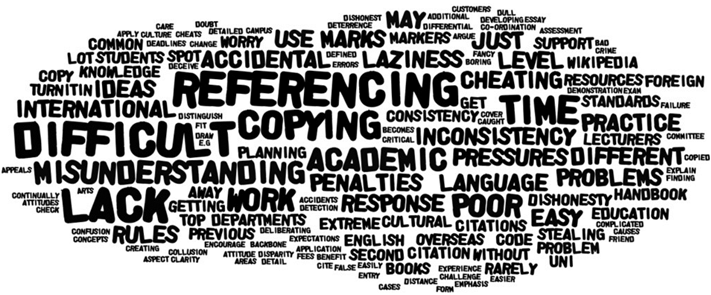

Accusations relating to the authorship of creative work are often aggregated with the single term, “plagiarising!”. Yet this should not imply a singular practice. Claims of ownership can be judged fragile for various reasons. So, regulation must attend to the different routes whereby the authorship of submitted work is, in some sense, unacceptably ‘shared’. However, particularly within educational contexts, the legitimacy of some routes towards this sharing might be judged quite innocent: a natural outcome of students seeking assistance through their research. A regulatory environment should acknowledge that there are totally legitimate ways in which students may find help when managing their learning – and distinguish them from ways that are illegitimate.

Accordingly, ‘help seeking’ is our parent concept for the present discussion of integrity offences. In the sections below, a basic vocabulary is proposed for distinguishing the different ways in which help seeking can cross a boundary – thereby inviting the accusation “plagiarising!”. What the remainder of this website then addresses is not the first category below (“text plagiarism”); instead, we consider cases where the submitted ‘text’ is not found but is created during interaction with others. So, we focus on understanding situations where help has been garnered through ‘an exchange with some other intelligent agent’. (We describe it in this ponderous fashion – rather than “help garnered socially” – to include certain forms of help negotiated with computational agents: machines that are increasingly capable of such apparently personalised dialogue and support.)

“Text plagiarism”

The term ‘text’ is used here generously. The object borrowed may correspond to the conventional understanding of ‘writing’, but its significant property in the present context is its material form – thereby rendering visible its shared nature. Rather than writing, it might be a diagram or a piece of computer code. This direct appropriation of material from someone else’s work without acknowledgement seems straightforwardly to be an offence – although strategic paraphrasing and patchwriting (Howard 1992), can make judgement of some cases more challenging. Nevertheless, this family of cut-and-paste textual offences remains the most familiar and common form of plagiarism – perhaps because it is the most readily detected.

Such plagiarism is easy to detect because the offending work is anchored to an independently existing source. It is potentially discoverable, should some sceptical audience choose to look for it. This possibility of exposing such plagiarising acts renders them somewhat transparent and, therefore, public in nature. Yet at the point of execution they are typically private, or autonomous. Because in such cases, there is no conspiracy, no negotiation, no contact at all between the plagiarising individual and the author whose work is plagiarised.

“Social plagiarism”

However, concern here is with a different form of plagiarism: one whose novelty and uncertain scale creates a more keenly felt sense of ‘crisis’. This is plagiarism that does implicate an intermediary and does, therefore, build upon exchanges with a helping agent. In these cases, the evidence of falsely claimed ownership is usually hidden from public view. For if there does exist an incriminating and unattributed source document, it is kept private by both the original author and the individual now making a false claim of ownership.

The phrase ‘social plagiarism’ has some currency, but is not widely adopted in the education literature. However, it is preferred here because it usefully integrates a variety of practices that seem to arouse a common concern and may require a common treatment. The practices that are integrated by this term include the following.

‘Contract cheating’. This is a more familiar term: in fact, it is the one that currently dominates discussion of what we mean by the more general ‘social plagiarism’. However, its limitations are that “contract” implies a commercial relationship and one with binding responsibilities for the partners. This certainly covers a serious and high profile set of offences: namely, situations whereby students purchase ‘text’ and then submit it as their own coursework. But the term excludes too many other related offences that also draw from an interpersonal exchange underpinning the claim of ownership.

‘Collusion’. Socially-mediated plagiarism may occur outside of commercial relationships. Formal definition proposes that the term ‘collusion’ refers to a concealed social interaction, the intended consequence of which is to mislead others (Crook and Nixon, 2019). The term therefore does identify an offence – a cheating against others. But (i) a colluding relationship would normally be more informal than implied by the term ‘contract’, and (ii) the claimed offence may not reside in a ‘product handover’ so much as in the harvested fruits of an interpersonal exchange. For example, this could include cases where a text submitted in a student’s name has been produced from within a consensual coordination with peers or family. Indeed, ‘collusion’ can fit cases where another person’s unattributed input to a submitted assignment text was a didactic (or simply ‘scaffolding’) conversation. At once, it should be apparent that academic prosecution of a collusion is often an inherently difficult process.

‘Artificial social intelligence’. This rather cumbersome phrase captures situations where a ‘text’ is constructed through interaction with intelligent software. Such a text may be judged a case of plagiarism because the unacknowledged input or re-drafting compromises the student’s claim of authorship. Evidently, such an offending ‘text’ has not arisen within (colluding) interactions between people. But the dialogic and computational sophistication of some software can capture a similar sense of human agency, and it can certainly allow quite significant levels of assignment help.

Why text and social plagiarism?

The underlying and common issue is how to judge an act in which ‘material’ has been borrowed and submitted, unattributed, as all or part of an assignment that is to be assessed. The above distinction then marks one contextual element that should be factored into any judgement of such an act: namely, the extent to which some practice under consideration involves an interpersonal relationship between material owner and material user.

Text plagiarism – where the material is harvested outside of any social relationship – might be thought less troublesome to regulate. There is a source and there is a reproduction from it: material-matching calculations can be invoked to help judge the presence of an integrity offence. Social plagiarism needs to be distinguished from this because it creates distinctive difficulties of evaluation. For these two reasons: (1) What is borrowed is ephemeral. There may simply be no source material available for that ‘matching’. It may exist, but not be in the public domain. Or, more challenging, it may never have existed in a physical form that can be independently scrutinised: whatever was borrowed was something that happened in an interpersonal exchange – ‘material’ that is usually very hard to evaluate as offending. (2) Where there does exist a physical record of the material borrowed from within social exchange; evaluation of offending may therefore need to consider the comparative responsibility of more than one actor.

Consideration here of both formats for plagiarism will be bypassing a whole set of problems that apply to both. These are expressed in contemporary debates relating to the credibility of such concepts as ‘author’, ‘ownership’ and ‘re-use’, considering how their contested status may complicate the very notion of academic offence (Howard, 2000; Pennycook, 1996). Discussions on the pages that follow can still proceed in reviewing a status quo, without becoming entangled in such controversy – although it will be returned to in the final section of this site.

How assessment practices have complicated help seeking

Recent discussion of assessment strategy has centred around a distinction between summative and formative designs. Summative assessment is diagnostic, it serves to warrant student achievement, and it therefore has a ‘feedout’ function. Whereas formative assessment is more concerned to create feedback; consequently it is sometimes termed ‘assessment for learning’ (Wiliam, 2011). Traditionally, summative assessment most often took the form of examinations or closed-book tests. However, Richardson (2015) has noted a gradual shift in higher education practice towards summative assessment being through open-book ‘coursework’. Such coursework is attractive for many reasons. Students generally prefer it to examinations (or prefer it mixed with examinations), grades tend to be higher (and so institutional performance tends to improve), time pressure is absent, expression of ideas need not be through writing alone, student anxiety may be reduced, variations in student health are less relevant, and the protracted nature of coursework can stimulate students towards deeper reflection and analysis.

However, an assignment that is protracted in this sense can mean feedout properties that are more troublesome to interpret. If the desired outcome of such an assignment is some measure of an author’s competence within the assessed discipline, then employers and other users of this feedout may expect checks on whether students own the work assessed. While text matching services such as Turnitin can deal with some of the uncertainties (defined here as ‘text plagiarism’), detection and evaluation is far more difficult for what we term ‘social plagiarism’. Unsurprisingly, individual academics struggle with defining ‘plagiarism’ (Maio et al 2019) while institutions then struggle to define the boundaries of legitimate help seeking for coursework assignments (Crook and Nixon, 2019).

The present website explores the extent of this problem, the various forms that help seeking can take, the motives driving questionable practices, and the strategies whereby such ‘questions’ can be raised.