A study by Bretag et al (2018) illustrates how student outsourcing of assignments can be associated with cultural factors – understood in two senses. First ‘culture’ as experienced in the students’ local and immediate study-world. Second, ‘culture’ as something individuals import from a broader legacy of experience – in which relevant models of authority and ownership might have been worked through elsewhere.

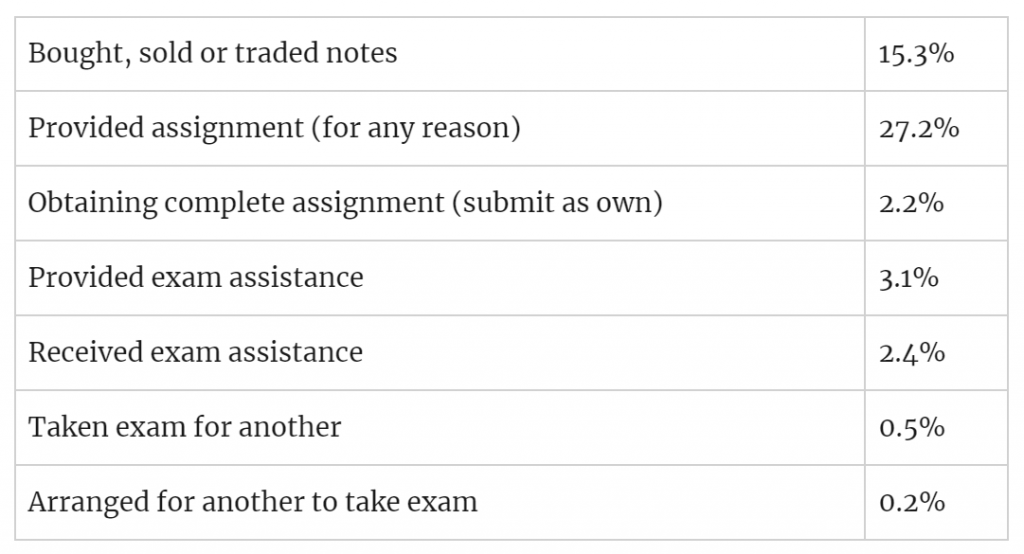

The researchers surveyed 14086 Australian university students (only 4.38% of that population), asking them to self-report on a ‘spectrum of outsourcing behaviours’. The plan was then to relate tendency to offend to their perception of other aspects of the cultural context. The proportion of students admitting these practices is shown below:

The survey also questioned forms of student dissatisfaction with their teaching and learning environment (the culture of students’ local study-world), as well as distinguishing students on various demographic characteristics, including gender, and speaking a language other than English (LOTE) at home. Some of the outsourcing questions were, arguably, ambiguous but clear offences were combined to identify a ‘cheating group’ (N=814) who could be compared with the remaining students. Assignment outsourcing behaviours were primarily correlated with high levels of dissatisfaction with the teaching and learning environment, perceptions that there were lots of opportunities to cheat in subjects, and the students’ LOTE status.

These are in this report cultural conditions of a ‘local’ kind (criticism of certain teaching and learning practices) and of a ‘global’ kind (language status). They are representative of circumstances which, if not recognised and managed, may afford a turn by students to outsourcing practices.

The LOTE status reflects Australian university recruitment from China and the Asian subcontinent. In media commentary on outsourcing problems, international students are often identified as being more likely to offend. This claim can be a source of tension. For instance, the NUS briefing for students on cheating comments:

There is a perception in the media that international students are more likely to use essay mills. There is no evidence to support this in a UK context; in fact there is very little data on the uptake of contract cheating in the UK at all and attempts to scapegoat international students as cheaters are dangerous and feed into wider xenophobic and anti-migrant rhetoric.

This position can be challenged. As outlined in these pages, there clearly is quite a large set of data on the uptake of contract cheating. There is also data of the kind sketched above that links language status to self-reports of outsourcing practices. Nevertheless, it is probably the case that there is a temptation among media commentators to make the easy leap from data of this sort to “international students as cheaters” rhetoric.

It would be very surprising if newcomers to a culture and language were not challenged by the demands made on them for academic writing. Indeed, essay mill authors often make sympathetic reference to the predicament of international students. Consequently, that those student might turn to professional help is also not surprising. Moreover, the tension for these students is not simply one of battling with the language of expository writing, there are also constraints arising from a more deeply-seated understanding of how language and communication works. In research on plagiarism awareness within such populations of international students, (Hu and Lei, 2012) have found that Asian students experience more difficulty in recognising offending cases – although when they are recognised there is no evidence that these students are more accepting of such offences.

Chien (2014) develops an argument that differences in sensitivity to these practices reflect varying cultural attitudes towards the idea that language might be ‘owned’. Pabian (2014) makes a similar case around the ways in which ideas are framed for students through educational practice in the Czech Republic. Here it is claimed that students tend to be excluded from knowledge construction, with copying being “integral to the dominant configuration” in that context. At the same time, Hu and Sun (2017) note how induction into plagiarism matters may be poor within those institutions from which international students originally graduated. In an analysis of policy texts from leading universities in China, the authors report little attention to the matter for undergraduate study and, for postgraduates, a strongly punitive approach with little evident effort to help cultivate good practices.

Cultural heritage may therefore be one aspect residing in ‘the conditions of study’ that afford help seeking, and the form that this help seeking takes may sometimes cross boundaries defined by the integrity proscription of a hosting educational system (see Pecorari and Petrić, 2014 for a fuller review). In short, cultural heritage may be relevant in shaping tensions in the moral choices that need to be made. For instance, cultural understandings may suggest that it is less of a personal shortcoming to outsource an essay than it is to admit to friends or family the humility of failing a course. As with other conditions discussed in these pages, the HE sector needs to be alert to these tensions and reflecting on ways they can be addressed.