We have established the scale of (contracted) social plagiarism practice and established that its scale is of some public interest. We also believe it can be established that the higher education sector has a challenge in addressing these matters. However, the extent of that challenge must depend not just on the scale of provision but also on the quality of what is provided. If the products are poor, then it could be argued that normal process of assessment will enforce a barrier to student progress where that progress is undeserved. It is therefore important to independently evaluate these products and judge if their quality is more than ‘poor’ in the way that we may hope.

How good are essays from mills?

As with the issue of ‘scale’, output from freelancers is more difficult to judge in relation to quality than is the case for the output of ‘mills’. The highly experienced ghostwriter, David Tomar (2012) has commented that for many writers – both freelance and industry-based – the experience and the money is often agreeable, while word of mouth can easily strengthen or weaken the reputation of a freelancer. However, even motivated authors can not necessarily promise quality writing. What is needed is some form of ‘mystery shopping’ investigation that can evaluate those ghostwritten products.

The academic Dan Airley made the first evaluation effort of this kind and his conclusions are often cited when these matters are discussed. Broadly they were reassuring to academics – in that what was commissioned turned out to be of low quality. Yet the exercise, while unique at that time, was very limited in scope.

A UK government education agency (Ofqual) sought similar data for the secondary school sector. The consultancy London Economics (2014) was invited to conduct a mystery shopper exercise. They commissioned three A level English essays and three History essays. All received low grades from independent examiners. However, the study was seriously flawed, because examiners were not blind as to the purpose of the research and were, therefore, likely to adopt a hostile attitude to the work examined.

Two more recent studies are careful to implement blind evaluation. They concern work produced for undergraduate and Masters-level customers. Medway et al (2018) report an exercise for undergraduate Management Science essays solicited from three providers, requesting that one should be of 2.1 degree class standard and the second a First class. To determine quality, essays were graded by 10 independent academics. The first essay just made, on marker average, the 2.1 standard requested, while the second fell just below the 2.1 standard, with only two examiners judging it to be the (requested) First class. This may still seem a reassuring outcome for essay mill customers. However, perhaps the most worrying feature of their report is the variation in grades awarded by the 10 independent (and experienced) markers. For the first essay, marks ranged between 40 and 75, while for the second marks ranged between 50 and 85.

Lines (2016b) reports a similar exercise, although one involving more providers. She purchased one undergraduate and one postgraduate history essay from each of 13 leading companies. Lines requested a ‘credit’ (65-74% US/UK equivalent) for the two essays. Three senior academics then graded them. Of the 13 undergraduate essays, only two failed, seven passed, three were awarded Credit and one a high Distinction. Six of the Masters’ essays failed, three passed, two were awarded Credit and two received Distinction marks. No significant plagiarism was reported. The researcher describes these results as “alarming”. Perhaps this is a fair judgement when put against the rigorous press warnings of the industry as a ‘scam’ and, if so, the alarm is a worrying one for university staff. However, a similar variation in the range of independent marks is apparent in the returns of the independent examiners. This is also ‘alarming’, albeit identifying a different quality management issue (marking unreliability) – but one that universities surely still need to address.

‘Quality’ also covers service delivery considerations, in addition to the academic standard of the assignment sold. Sutherland-Smith and Dullaghan (2019) have investigated this by testing how persuasive were the three dimensions of ‘informativeness’, ‘credibility’ and ‘involvement’ identified by Rowland et al (2018) in their analysis of website sales rhetoric. They ordered a variety of 54 assignments from 18 sites and experienced a wide range of service disappointments: premium and standard levels were not noticeably different, turnaround was sometimes longer than advertised and final price was higher than those predicted as ‘typical’, briefs were often ignored. Although the authors indicate that 50% “failed to reach the university pass standard”, it is not clear how this assessment was conducted.

Essay mills under review

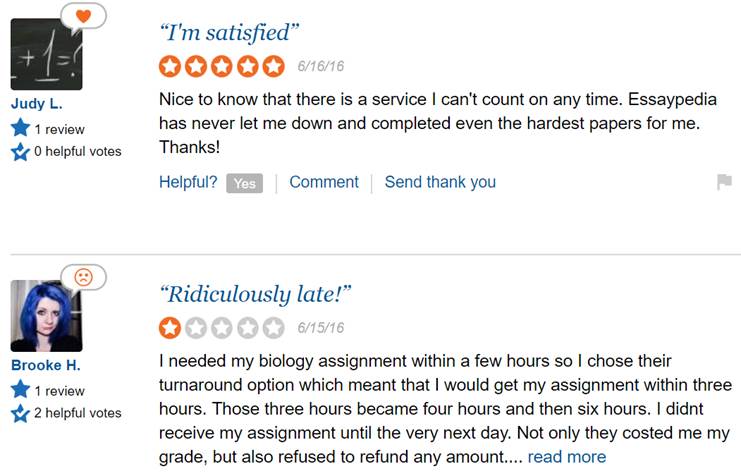

As with other marketplace products, the work of essay mills can be liable to user review. Intending customers may then estimate the potential quality of work commissioned by accessing online review sites. Reviews are generally text-based although a video review may be more persuasive. There are two reasons to be cautious about both formats. The first is that text review sites themselves may be bogus. For instance revieweal.com is very coy about its authority and identity; it also gives consistently high reviews. Secondly, the reviews posted may be bogus: they may be positive reviews written by the owner of the site referred to (such misleading practices are highly likely for testimonials on the service websites themselves), or they may be negative reviews written by competing sites.

For instance suspicions of authenticity might be aroused when reviews are significantly bimodal (see above) – with significant numbers of 5* reviews coupled with significant numbers of 1* (e.g. Myassignmenthelp). This surely should not happen. But 1* may be real customers reporting their real experience while 5* would be what site owners would post. Similarly the text of positive reviews can often feel suspiciously similar in vocabulary and tone. For essaypro.com as reviewed on sitejabber, we find a surprising overlap of content. Moreover, there are hints of patchwriting. So, in the second sentence: Justin B. awards 5* and comments:

Their writers are professionals who can handle topics of any complexity. I am glad to be EssayPro’s customer.

while Sarah Pritts (also 5*) comments:

Their writers are real professionals, who can handle papers of any complexity. I am a loyal customer of EssayPro for over a year now.

Yet, if the same company is compared across different (but authoritative) review sites, it is possible to find similar patterns of judgement. For instance, Edubirdie.com receives 36 reviews on trustpilot.com which involve 69% 5* and 19% 1* the same site on sitejabber.comreceives 97 reviews, with 67% at 5* and 16% at 1*. Some of the reviewers have posted for other essay mill sites but it is also the case that some have reviewed very different types of product on the same site. Together these observations might suggest reviewing can provide some basis for choice and some assurance of quality. But, if so, it would be wise to scrutinise the review trail carefully.

In sum, the popular expectation is that contract companies do a poor job and their use represents a risk for students. Review sites indicate that their unprofessional practices can extend to faking testimonials. But both review sites and research findings provide warnings to universities that the products of these sites can often be of a standard that will achieve pass grades – sometimes higher.