The six pages of this website section consider the variety of ways in which ‘social plagiarism’ can be described. What we mean by this phrase is a false claim of ownership applied to a submitted assignment that has been constructed, not by the student alone, but in collaboration with some other agent. The overarching questions then become: Who can act as such an ‘agent’? And by what means, and with what motives, is such a collaboration established? In later sections we shall also consider the scale, quality, detection and regulation of such collaborations.

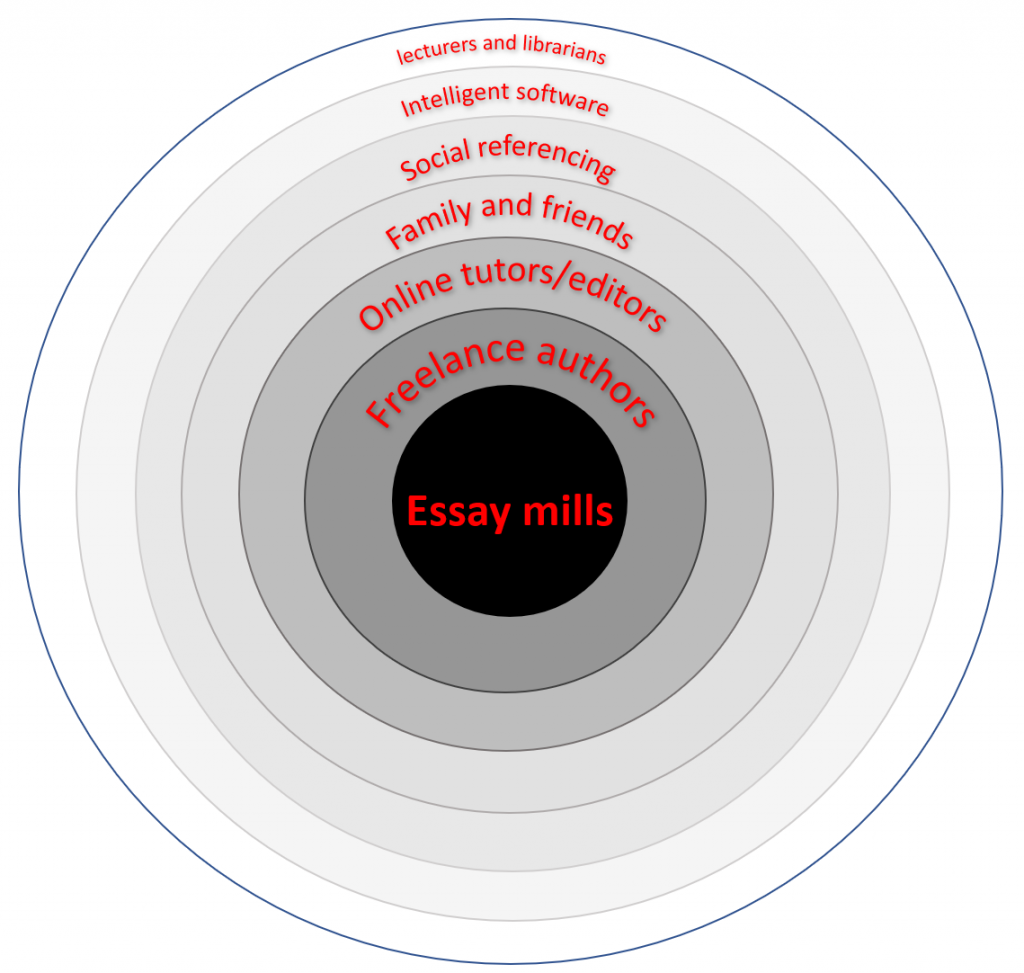

Although the term ‘plagiarism’ will be applied freely across the examples discussed here, a real problem for universities is the uncertainty as to when such a plagiarism accusation is appropriate. There is a danger of supposing that the only circumstance needing consideration is the iconic case of the ‘essay mill’. Certainly, there is little to discuss regarding the propriety of a situation in which a student submits – in their own name – an assignment that has been purchased from an internet website. But such cheating through authoring ‘contracts’ must be viewed as one end point of a continuum. That continuum is one of help seeking. It might usefully be visualised in a manner that maps the uncertainty felt about whether academic integrity has been violated or not.

We suggest here that such a continuum of offending is visualised as a kind of onion. The outer layers represent forms of help giving and help seeking that could be innocent or benign. But as one moves towards the core, that judgement is increasingly challenged.

In the diagram above, this uncertainty is represented in shades of grey. At the centre is the very dark space of the essay mill. But on later pages of the present website, we describe other forms of help that are more difficult to judge. So, if we ask what is the gradation in this diagram is gradations of? The answer is not simply “from serious misconduct to less serious”. Because we may suppose that each layer offers both very serious and very benign misconduct opportunities. Therefore, the shades of grey illustrate and increasingly concealed form of practice and our increasingly uncertain understanding of what goes on there – and, accordingly, an uncertainty about how to go about protecting, promoting and exercising academic integrity in that space.

- Freelance authors advertise bespoke assignment writing

- Online tutors independently, or through websites, advertise personal academic support

- Family and friends support assignment work through informal engagement

- Social referencing occurs when help is harvested from social media sources

- Intelligent software simulates tutorial dialogue or enacts computations

- Lecturers and librarians are the formal institutional source of student help

They are all social – in that they involve potential plagiarism arising out of an interpersonal relationship (the penultimate layer of ‘intelligent software’ stretches this definition but still deserves consideration in the same family). However, the sense of a ‘contract’ is less compelling as one moves towards the outer layer of the onion. At least this is the case if the term ‘contract’ implies a commercial, financial, and potentially impersonal relationship between the partners. For these reasons we prefer the term ‘social plagiarism’ to ‘contract cheating’

In the white space of the outermost layer we have placed tutors and librarians. They are the official agents of help-giving to university students. However, the purity of this final white space may also be a matter for consideration. In feedback from students contributing to our own research it was not uncommon to find troubled references to the quality and quantity of such help. This is apparent in the following comments regarding obstacles to effective coursework:

Not enough guidance was provided. Once a person is given their assessment title, the member of staff doesn’t provide any additional assistance or guidance which forces an individual to guess and estimate the appropriate materials to use, the level of research to conduct and the style of writing to employ.

Sometimes lecturers respond to your emails with vague replies which I find really frustrating. It’s usually few words with grammatical errors which does not really answer the question.

Sometimes when you need help from the teacher, you realise their office hour is on a particular day, and if you already missed that, you may just think to deal with it by yourself.

No conversation with tutor – she gave minimal generic feedback on proposal and contradictory email follow up.

Some tutors are more helpful than others, the unhelpful ones do not want to answer your questions and send you off to do more research instead of helping – so you just go back the next week with the same question

These quotations illustrate concerns that are, perhaps, familiar. They address poor access arrangements. However, there have also been concerns of the opposite kind: namely, staff who are perceived as giving too much or too selective help:

I know of one of my friends who got her personal tutor (who she is very close with) who was also the module convenor of one of her modules to tell her the answers to an exam as well as what she needed to write to get a first for her coursework

My tutor sees a peer to discuss their assignment every time, I on the other had cannot get five minutes alone to clarify their feedback.

In the management of assessment, it would be unusual to discuss tutor help in terms of social plagiarism. However, comments such as those above are a signal that staff help giving might be absorbed into the same kind of ‘fairness discourse’ that students apply to other more questionable agents of assignment help. These comments also might be a warning to universities that help seeking from staff is always likely to be a relationship that is difficult to manage. Maximum transparency in relation to expectancies is the goal to strive for.

In the following pages of this Section we consider the various practices that realise help seeking for students. The purpose is to consider the form that they take but also to recognise the integrity dilemmas that they prompt