The most infamous mode of social plagiarism is that associated with the essay mill. What mills typically claim to do may technically be innocent (furnishing example assignments). In practice, their service becomes a poisonous agent within higher education when the fate of such ‘mere examples’ is their submission for assessment in some customer’s name. Unfortunately, the integrity challenge that universities face is greater than the task of identifying the products and practices of these mills. If those businesses are unquestionably ‘dark’, there are shades of grey surrounding them.

This penumbra of social plagiarism could be mapped in various ways. For instance, if essay mills are a matter of ‘identity deception’, then exam stand-ins would deserve discussion under the same heading. Newton and Lang (2016) have discussed social plagiarism in a way that incorporates such cases. Here, we will be more circumspect. We suggest that academic offences become ‘grey’ according to (i) the dynamic of the contract in ‘contract cheating’ and/or (ii) the depth of the social in ‘social plagiarism’. The darkest case is surely when the contract involves the minimal possible social engagement between contracted author and the student partner (or customer). This is the case of some anonymous author mechanically responding to some anonymous customer’s request to deliver on an assignment title. Evidently, a contract could involve a more balanced involvement of these two partners. Therefore, some sites (e.g., assignmentpedia) invite the uploading of assignment drafts – the task as so far completed by students. There is then a “partial review facility” whereby that draft can be developed by a chosen site author – with suitable discussion. It is for those examples that ‘collusion’ seems a better label than ‘contract cheating”. Perhaps ‘contract collusion’?

Making freelancing visible

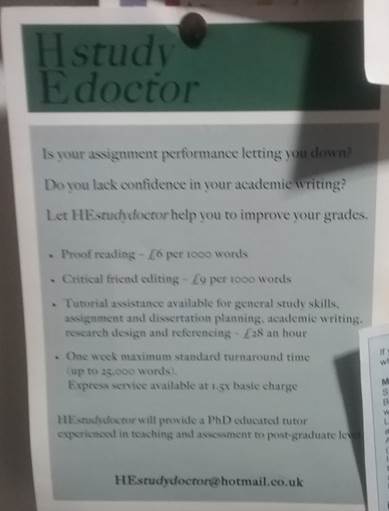

Classified ads are a well-known format for soliciting freelance work. There is no reason that such work should not be academic in nature and no reason customers should not be students struggling with assignments. Such ads need not be in the traditional newspapers – they may be found on the noticeboards of university campuses. Here is one from our own:

However, the internet provides a more versatile space for such trading. Thus the widely-used ‘Craigslist’ includes a section for writing/editing/translation that can be searched by different areas of the country for help. Lancaster (2019) reports that in October 2018 there were 197 authors advertising writing services on Fivrr.com. The site ‘Freelancer‘ allows jobs to be posted and users can bid for completing them. These jobs often include academic assignments. The idea of recruiting writing in this way has been discussed by users. One comments:

As a writer who has used CL to get clients I can say that I’ve built up a large clientele because I get the work done on time and I follow certain standards (keep to the quote even if it takes longer than I quoted, no late papers, no plagiarism, etc.) I can’t speak for everyone who advertises on CL (someone is flagging my posts) but you can definitely find people who are willing to work for you and keep working for you.

Amazon’s crowdsourcing service, Mechanical Turk, offers a template for ‘human intelligence tasks’. One commentator gives the example of someone submitting “please re-write the following sentences” – which turn out to be about recipes. It is hypothesised that the contractor is plagiarising a cookbook. Evidently commissions might include intelligent tasks may have greater scope – whose products might be submitted for educational assessment. An air of innocence might be created if the agents are not informed that their work might become an act of plagiarism. Harris and Srinisvasan (2012) have considered the willingness of crowdworkers to violate academic integrity. They report that in two samples of 200 workers, 79% agreed to provide their work for assistance on exams or homework assignments.

Tutorial relationships: online

The examples above may have only limited involvement of internet services. Tutors may be recruited through traditional classified advertising rather than online. Or if they are recruited with digital communication, then they may do their work ‘remotely’ – receiving and instruction and sometime later delivering the product. However, the internet has furnished not only a means of recruitment but also a medium for more fluid collaboration. Indeed, a sense in the customer that they are seriously involved with the development of an assignment submission may help neutralise their concerns about academic integrity.

A service that provides such personal or intimate tuition is much more difficult to judge in terms of its threat to academic integrity. Some services do advertise help that includes both tutoring and writing, but others are more cautious. For example, The Profs is a site that does not claim to help in the actual construction of work that will be submitted by a client for assessment. They therefore can be quite explicit about who they are and what they charge (£70/hour), while being quite implicit about what level of support their service could potentially offer. Testimonials give some hint:

My daughter got help from Veronica L Jefferies for her dissertation I couldn’t have asked for a better person to help her. The Prof was patience and spent very long time going through it all with her. In the end she not only helped so much but made my daughter very confident.

The example invites several important reflections. First, is the testimonial a fake? “The Prof was patience and spent very long time” suggests a writer with English not as first language. While this may signal something about the parent it may also signal something about service managers writing their own reviews. Second, endorsement from a parent is a reminder of the increasing expectations and pressures that families can create on their offspring students. Third, the service product is a dissertation: one which a professional tutor has “spent a very long time going through” – is the submission of this work violating institutional expectations on collusion? For instance, my own university School offers a maximum tutorial allocation that will “go through” one chapter (only) of a dissertation before submission.

Promotional videos from The Profs imply that these tutors are well qualified with postgraduate degrees and the founder was himself someone who had always aspired to university lecturing. With employment difficulties for postgraduates (and casual academic staff), there is evidence that this draws some to contract writing (Eden, 2020). Whatever other challenges such examples create, one must be a concern among onlookers (parents for example) that the sector is not meeting its tutorial responsibilities with sufficient intensity.

If services are recruited from sites such as gumtree, tutors do not have to declare the depth of help they will give and customers may feel free to dictate that. Companies that recruit from websites have to be more careful what they advertise. However, again their testimonials can be a way of massaging expectations without seeming to cross integrity red lines. For instance, the company Spires includes this endorsement:

Excellent very patient tutor who showed me how I could interpret data similar to what I had collected and how I might interrogate it a bit further. Then I went on to do it all by myself. What a sense of achievement. Good service and great value.

The student/customer (whether authentic or not) establishes for other potential customers the idea that help interpreting “data similar to what I had collected” will have pretty much the same useful value as interpreting data that I actually did collect.

These examples refer to ‘professional’ services for tutorial support. The extent of uptake and the depth of assignment help that they might involve remains uncertain. However, there is even more uncertainty over the ‘informal’ help that might be furnished by friends and family. As a signal of the possible scale of this, a recent study reports that up to a quarter of UK secondary school students received private tuition.

Proofreading as ‘tutoring’

In our own project, most of the campus noticeboard postings we found that advertised academic help were directed at proofreading or “help with writing”. Again, there are many agencies that offer this service, some trading on the brand names of distinguished universities. Sites that advertise such services may often hint at the possibility for depths of attention that go further than simply spotting typos. Thus what might be implied by Regent Editing’s offer:

We carefully examine your PhD thesis paper for logical accuracy, relevance of references, appropriateness of titles and precision of graphs/tables.

Editing that goes beyond superficial textual features (‘proofreading’) or beyond expression and consistency (‘copyediting’) is sometimes termed ‘substantive’ or ‘structural’ editing. Lines (2016b) discusses these distinctions, concluding from a survey that 44 out of the 50 websites that offered editing services to thesis authors did offer substantive editing – only six declaring that they definitely would not. Her study draws on her own experience as the owner of an academic editing service in Australia and the communications she had with clients around a range of academic writing integrity. She summarises:

Substantive editing is a particularly insidious form of plagiarism since it has received so little attention by universities, it is seen as less serious than other forms of plagiarism, it requires high levels of vigilance to detect and there are no deterrents in place.

Kim et al (2018) report of survey of both student and staff understandings of where the boundaries exist for depth of editing that is acceptable. They report widespread variation in understanding the propriety of the various services that a student might use. They also find further differences in judgement associated with the international status of the student. Moreover, faculty often expressed the view that “specific contexts and instructor’s expectations should be taken into consideration”. However, some would argue that faculty do not have that luxury of discretion. Good practice relating to editing should be declared in university regulations. However, universities may differ in how they frame the boundaries of what is appropriate. For example, one Russell Group institution may be unusual in banning any use of editing services:

In a University context responsibility for proof-reading student work prior to its submission for assessment rests with the individual student as author. This longstanding principle cannot be compromised by the spread of professional proofreading services advertised to students, or any ambiguity amongst students and staff as to what constitutes acceptable practice.

The sector as a whole may not be helped by significant variation in policy across institutions.